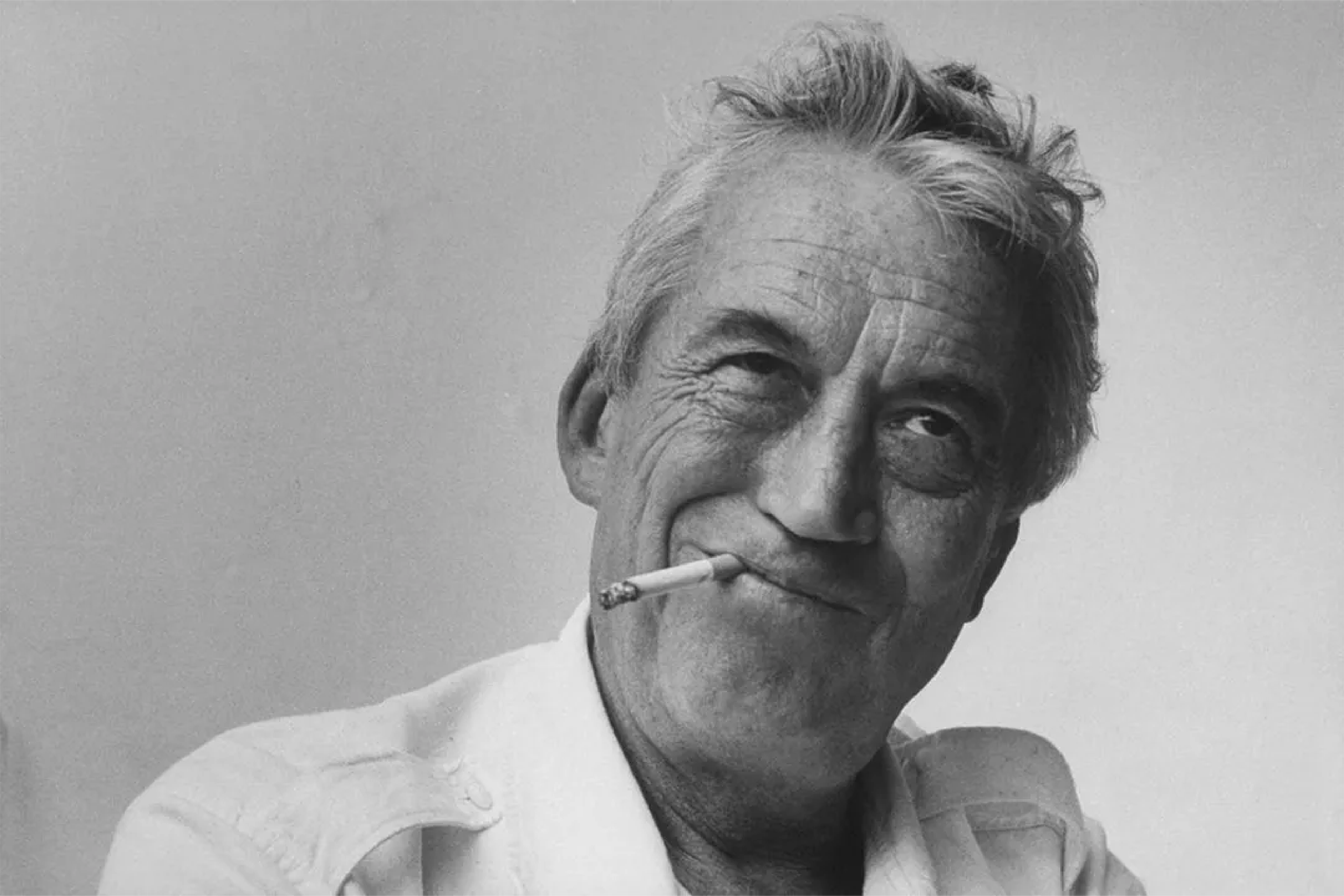

Before Rhythms of the Night transformed Las Caletas into a stage of myth and artistry, this hidden cove was already part of cinematic history. Its story begins with John Huston, one of Hollywood’s most daring filmmakers.

Huston built his legacy directing masterpieces such as The Maltese Falcon, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, The African Queen, and Prizzi’s Honor. His films revealed the struggles, passions, and contradictions of human nature, and his restless spirit drew him beyond Hollywood. In the early 1960s, Huston chose Puerto Vallarta to film The Night of the Iguana, a production that not only earned international acclaim but also placed the small fishing town on the world’s cultural map.

Captivated by the raw beauty of Puerto Vallarta's beaches, Huston sought refuge and inspiration in Las Caletas, a secluded paradise accessible only by sea. In his writings from the early 1980s, Huston described nights where wild creatures roamed his garden, mornings filled with parrots wheeling across the treetops, and seas alive with rays, whales, and dolphins. He called Las Caletas “an island,” a sanctuary isolated from roads and noise, where nature itself dictated the rhythm of life.

Here, the filmmaker found more than solitude—he discovered a sanctuary where jungle, ocean, and imagination converged. Long before Rhythms of the Night, Las Caletas had already become a place where art, nature, and storytelling intertwined.

His reflections, preserved in a letter from that time, reveal how much the cove became part of his spirit: a place of healing, inspiration, and tranquility.

For the better part of the last five years I have been living in Puerto Vallarta, Jalisco, Mexico. When I first came here, almost thirty years ago, Vallarta was a fishing village of some two thousand souls. There was only one road to the outside world - and it was impassable during the rainy season. I arrived on a small plane, and we had to buzz the cattle off a field outside town before setting down.

Over the years | came back to Puerto Vallarta a number of times. One of those times was in 1963 to film The Night of the Iguana. It was because of this picture that the world first heard of the place. Visitors and tourists flocked in.

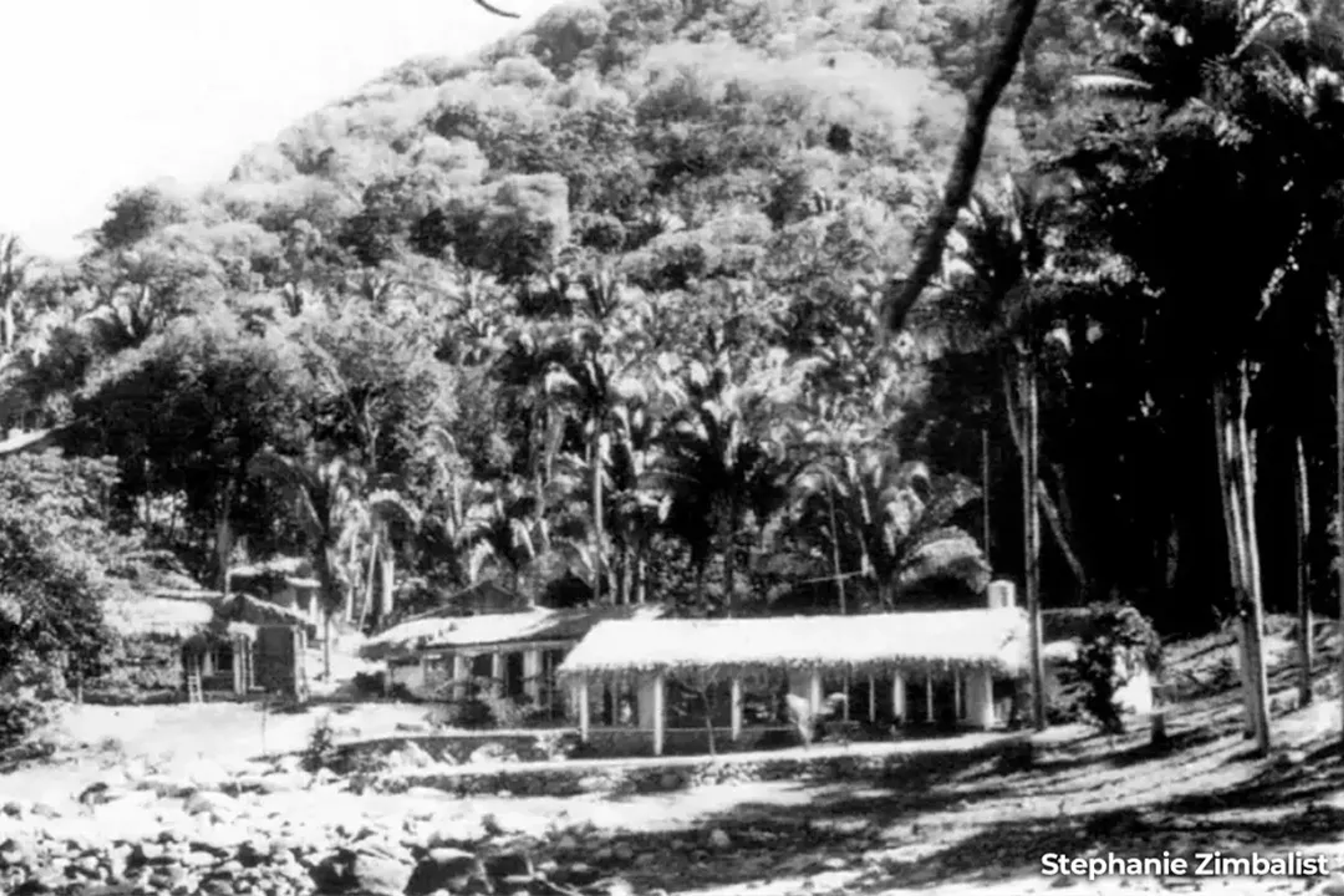

I am now living in Las Caletas, where I've leased one and a half acres from the Chacala Indian Community, the Mexican government has granted these Indians a long stretch of coast and a large interior region. To get to where I live you drive about fifteen miles south of Puerto Vallarta to a small fishing village called Boca de Tomatlan, where the highway leaves the sea and turns inland over the mountains. From Boca you take a panga (an open fiberglass boat with an outboard motor) south some thirty minutes to Las Caletas.

I have my place on a ten-year lease, with an option for another ten. After that, the land and whatever I've built on it go back to the Indians. Las Caletas is my third home. There are no roads to it, and it's unlikely there will ever be - the nearest village is about half an hour away by jungle trail. Las Caletas faces the sea and its back to the jungle, for this reason one thinks of it as an island.

Life here is lived in the open. At night wild creatures come down to inspectthe changes l've made in their domain: coatimundias, opossums, deer, boars,ocelots, boas, jaguars. We find their spoor or trails in the mornings. Flocks of frenetic parrots come winging in at first light, full of talk. They climb, dive, wheel as one bird, alight in the treetops, all talking. They take off, do another quick turn or two and disappear - talking.

After sunrise the jungle quiets down, but there is always something going onat sea. Pelicans in tandem, skimming the waves - gulls and other seabirds, diving when the surface of the bay seethes and boils with sardines or schools of other small fish. There's. a manta ray who performs regularly about fifty yards offshore. He always jumps twice. The first time is to get your attention. Then he throws all three thousand pounds of himself so high out of the water that you can see the freckles on his white underbelly. Gray, humpback and killer whales and porpoises ply the offshore waters. We're trying to keep a record on the grays because this is the farthest south they've ever been seen.

The winters are sparkling clear. There is almost no rain for nine months. By spring the jungle greens have faded to olive drab. In late June the clouds begin to gather. They thicken and lower until they're halfway down the mountainsides. The atmosphere gets heavier and heavier. Then one day the heavens open and the torrential rains beat down. Instantly there are explosions of color throughout the jungle: orchids, birds of paradise, all manner of bromeliads. And every night there's an electricity display out at sea, lighting up the horizon like a great artillery duel between worlds.

Now that I'm of a certain age, I'm following a piece of old Irish advice in going to live by the sea: 'It stops old wounds from hurting. It revives the spirit. It quickens the passions of mind and body, yet lends tranquility to the soul.'